HIMB Study Tracks Tiger Sharks to Maui Mating Hub

A team of shark researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa has solved a long-standing mystery, identifying the first-ever documented mating hub for tiger sharks. The new study, led by the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) Shark Lab, utilized six years of acoustic tracking data to pinpoint Olowalu, Maui and the nature of tiger shark mating. This challenges the conventional understanding of tiger sharks as purely solitary animals, revealing a predictable seasonal convergence of mature males and females that coincides with the humpback whale calving season in Hawaiʻi.

Shark turf wars have profound effect on where seabirds nest, reveals study

Scientists discovered a “critical” link between seasonal nesting and the movements of the marine apex predators in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. They found that the annual summer arrival of fledgling seabirds at French Frigate Shoals (FFS) concentrates tiger sharks in specific areas, forcing other species – including grey reef and Galapagos sharks – to “drastically” shift their own habitat use to avoid being attacked. The research team say their study highlights an indirect connection between terrestrial and marine ecosystems, showing that the presence of a seasonal food source – fledgling seabirds – influences the behavior of an entire community of apex predators. Using acoustic transmitters, the team by scientists from the University of Hawaii Mānoa Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) Shark Lab tagged 128 sharks. They tracked their movements around FFS over two years. The researchers compared shark habitat use during the seabird season and the off-season, observing “clear” behavioral shifts. Study’s lead author Chloé Blandino, of HIMB Shark Lab, said: “We discovered that tiger sharks gather around small islands in summer to hunt fledgling seabirds, which, in turn, forces other smaller sharks to adjust their habitat use. “It was exciting to see our predictions line up so closely with reality; it’s a clear example of how a seasonal food source can influence habitat use by an entire predator community.” The research team found that when tiger sharks are present, the smaller grey reef sharks avoid those areas completely to reduce the risk of being eaten. Galapagos sharks shift to different times or zones within the atoll to minimize competition. Once the seabirds disperse, the tiger sharks move on and the other shark species return to their original habitats.

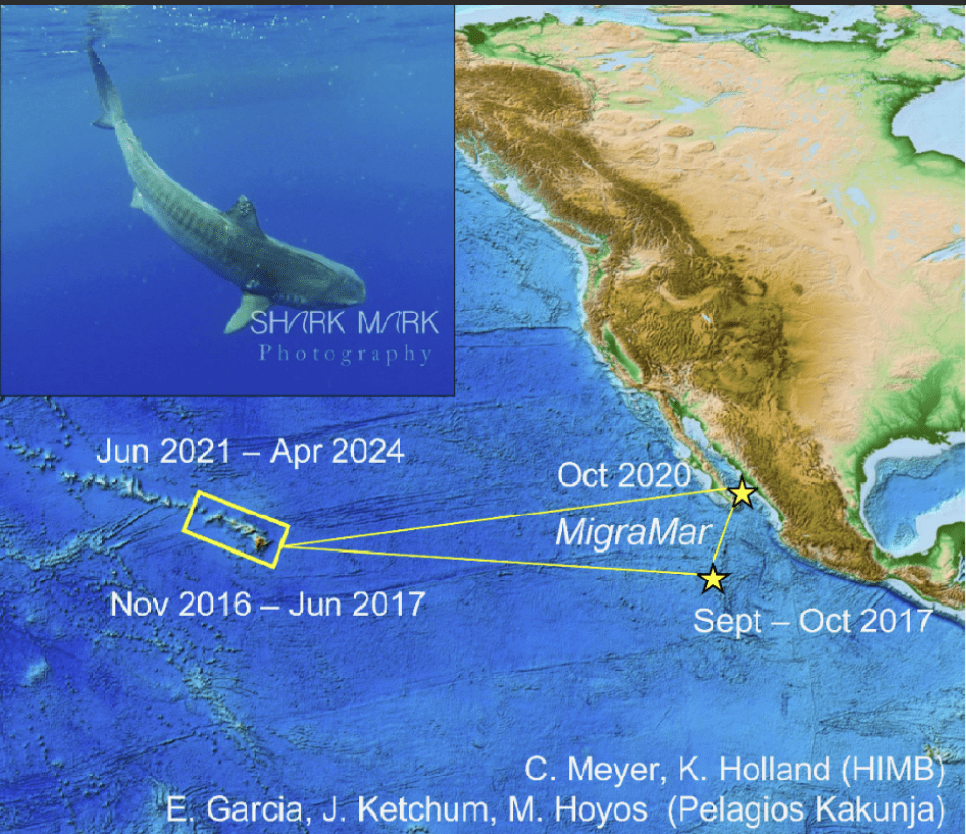

Long term tiger shark movement Hawaii-Mexico-Hawaii

PacIOOS’ PIRAT Network and the HIMB Shark Lab have identified the first record of a tiger shark round trip migration between Hawaiʻi and Mexico. In 2016, the Shark Lab tagged a mature female tiger shark off of Mokoliʻi, Kāneʻohe. Less than a year later, it was detected at the Revillagigedo Islands and Cabo Pulmo, BCS, Mexico, on equipment maintained by Drs. Mauricio Hoyos and James Ketchum, from Mexican non-profit Pelagios Kakunjá. After 3 years, this shark eventually returned to Hawaiʻi, where it has been detected consistently until early 2024. Identifying long-range movements like these are often difficult, unless the researchers involved happen to collaborate directly and actively share data. However, these researchers shared their data with the PIRAT Network and partner organization Migramar, which led to the realization of this discovery between the Shark Lab and Pelagios Kakunjá. Not only is this a valuable piece of evidence that advances our understanding of this highly migratory species (and also raises new questions), but it illustrates the importance of data sharing initiatives in aiding researchers seeking to maximize the outcomes of their work. PIRAT checks for cross-matches like these every 4 months, so stay tuned for new matches! [Image credit: Shark Mark Photography, PIRAT]

UH Researchers Turn Sharks Into Oceanographers, In Two Oceans

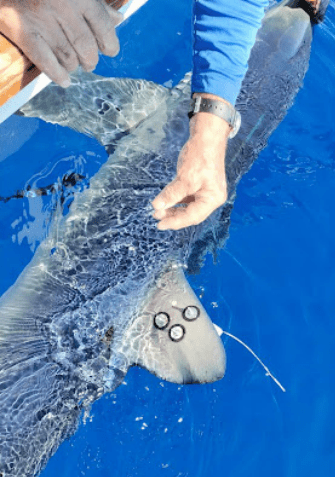

Kim Holland, Research Professor at UH Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) and founder of its Shark Research Lab, together with colleague at the University of the Azores, deployed the first ever bathygraph tag in the Atlantic ocean in recent weeks, on a 3-meter long blue shark near the island of Faial. Part of an expanding “Sharks as Oceanographers Program” funded by the Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System (PacIOOS), the bathygraph tags used in this study are the first to be deployed on any type of fish, and as the program name suggests, the tag effectively turns a shark into an oceanographer, enabling it to record ocean temperature as it roves the water column and transmit the data via satellite when it returns to the surface. The tags allow researchers to access the data in near-real time, and are designed to fall off after roughly four months. “The bathygraph tags are an example of the increasingly sophisticated animal telemetry tools that are available to scientists,” explains Holland. “These tags are now able to tell us not only where the animal is, but they can also describe the environment that it is experiencing. In the future this will include parameters such as oxygen content and plankton density.”

Sharks Critical to Ocean Ecosystems, More Protection Needed

Shark conservation must go beyond simply protecting shark populations—it must prioritize protecting the ecological roles of sharks, according to new research at the University of Hawaiʻi. The largest sharks of many of the biggest species, such as tiger sharks and great whites, play an oversized role in healthy oceans, but they are often the most affected by fishing. The big sharks help maintain balance through their eating habits. Sometimes their sheer size is enough to scare away prey that could over-consume seagrass and other plant life needed for healthy oceans. Sharks also help shape and maintain balance from the bottom-up. That means a variety of sharks in a variety of sizes are needed, yet their many and diverse contributions are under threat from overfishing, climate change, habitat loss, energy mining, shipping activities and more. The study, led by Florida International University (FIU) with partners at UH Mānoa’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) and others, was published in Science and sheds new light on how sharks- and their size- contribute to healthy oceans. “New tools and technologies have enabled us to make huge strides in recent years in understanding the diverse—and critically important—roles that sharks play in the world’s ocean ecosystems,” explains Elizabeth Madin, co-author of the paper and associate professor at HIMB. “It’s clear now that protecting shark populations is a wise investment in ocean health, and one which ultimately benefits people and the planet.”

HIMB Shark Lab Spots 30-foot Whale Shark off Kāneʻohe Bay

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa researchers spotted the world’s largest fish species, a 30-foot whale shark, a mile off Kāneʻohe Bay near Kualoa Ranch on November 2, 2023. Researchers from the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) Shark Research Lab were returning from conducting field work when they spotted seabirds flying over what they suspected was a bait ball, where small fish swarm in a tightly packed spherical formation near the surface while being pursued and herded by predators below. Mark Royer, a HIMB shark researcher, went into the water to see what sealife had gathered to feed and was surprised to see the whale shark. “It is surprising,” said Royer. “[Whale sharks] are here more often than we think, however they are probably hard to come across, because I didn’t see this animal until I hopped in the water.”

Hammerhead sharks hold their breath on deep water hunts to stay warm

Scalloped hammerhead sharks hold their breath to keep their bodies warm during deep dives into cold water where they hunt prey such as deep sea squids. This discovery, published today in Science by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa researchers, provides important new insights into the physiology and ecology of a species that serves as an important link between the deep and shallow water habitats. “This was a complete surprise!” said Mark Royer, lead author and researcher with the Shark Research Group at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “It was unexpected for sharks to hold their breath to hunt like a diving marine mammal. It is an extraordinary behavior from an incredible animal.”

New UH Vessel to Expand Marine Research and Conservation Efforts

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa will welcome a new research vessel Imua in fall 2023. The 68-foot semi-displacement aluminum catamaran will be used by a team of 12 researchers at the UH Mānoa Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), including two Coast Guard-certified captains who will operate the vessel. The All American Marine, which specializes in constructing vessels, was awarded the contract to build Imua. Imua is a part of the $50 million gift from Dr. Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg to HIMB earlier this year to improve Hawaiʻi’s ocean health. The knowledge gained from science missions on this vessel will directly support the management and conservation of Hawaiʻi’s marine resources.

National Geographic Docuseries Features UH Shark Scientists

The majority of shark research content is narrated and led by male scientists, and enthusiasts. The focus of a new National Geographic docuseries titled “Maui Shark Mystery,” follows the stories of three female marine biology graduate students at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. The series aims to gain a better understanding of how and why tiger sharks utilize marine habitats around Oʻahu and Maui Nui. The three women featured from the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) Shark Research Lab are Paige Wernli, a PhD candidate; Chloé A. Blandino, a shark husbandry research specialist; and Julia Hartl, a PhD student and research assistant. Filming this documentary gave the UH Mānoa graduate students a chance to advance themselves in science, and the opportunity to inspire the next generation of up-and-coming scientists through exemplifying their capabilities as women in shark research.

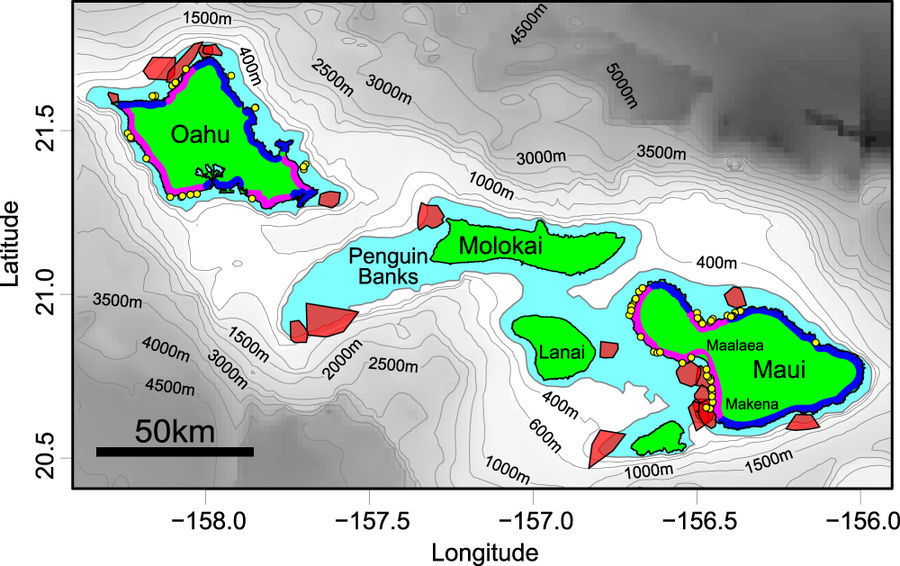

Habitat geography around Hawaii’s oceanic islands influences tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) spatial behaviour and shark bite risk at ocean recreation sites

Habitat geography around Hawaii’s oceanic islands influences tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) spatial behaviour and shark bite risk at ocean recreation sites

We compared tiger shark spatial behavior among 4 Hawaiian Islands to evaluate whether local patterns of movement could explain higher numbers of shark bites seen around Maui than other islands. Most individuals showed fidelity to a specific ‘home’ island, but also swam between islands and sometimes ranged far (up to 1,400 km) offshore. Movements were primarily oriented to insular shelf habitat (0–200 m depth) in coastal waters, and individual sharks utilized core-structured home ranges within this habitat. Overall, our results suggest the extensive insular shelf surrounding Maui supports a fairly resident population of tiger sharks and also attracts visiting tiger sharks from elsewhere in Hawaii. Collectively these natural, habitat-driven spatial patterns may in-part explain why Maui has historically had more shark bites than other Hawaiian Islands.

Shark Study Helps Explain Higher Incidence of Encounters off Maui

Shark Study Helps Explain Higher Incidence of Encounters off Maui

Important research out of the University of Hawaiʻi is providing state leaders with critical information to better develop outreach and awareness efforts to minimize possibly dangerous encounters with tiger sharks. After a spike in shark bites off of Maui in 2012 and 2013, the State Department of Land and Natural Resources turned to the experts at the UH Mānoa Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB). After years of work, UH shark researchers Carl Meyer and Kim Holland and a team of students completed an important study revealing movement patterns of tiger sharks around Maui and Oʻahu.

Deep Sea Sharks are Buoyant

Deep Sea Sharks are Buoyant

Scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and University of Tokyo revealed that two species of deep-sea sharks, sixgill and prickly sharks, are positively buoyant—they have to work harder to swim downward than up and they can glide uphill for minutes at a time without using their tails. Positive buoyancy may be a physiological strategy enabling these sharks to exploit deep, cold habitats with limited food resources. Their results were recently published in PLoS ONE.

Study Reveals Tiger Shark Movements around Maui and Oʻahu

Study Reveals Tiger Shark Movements around Maui and Oʻahu

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa researchers are using tracking devices to gain new insights into tiger shark movements in coastal waters around Maui and Oʻahu. The ongoing study reveals their coastal habitat preferences. “We are seeing a strong preference for coastal shelf habitats shallower than 600 feet,” said co-lead scientist Dr. Carl Meyer. “Although these sharks also roam far out into the open ocean, they are most frequently detected in the area between the coast and the 600-foot depth contour that is up to 10 miles offshore around Maui.”

Researchers Reveal Insights into How Sharks Swim, Eat and Live

Researchers Reveal Insights into How Sharks Swim, Eat and Live

Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and the University of Tokyo outfitted sharks with sophisticated sensors and video recorders to measure and see where they are going, how they are getting there and what they are doing once they reach their destinations. Scientists are also piloting a project using instruments ingested by sharks and other top ocean predators

to gain new awareness into these animals’ feeding habits. The instruments, which use electrical measurements to track ingestion and digestion of prey, can help researchers understand where, when and how much sharks and other predators are eating, and what they are feasting on.

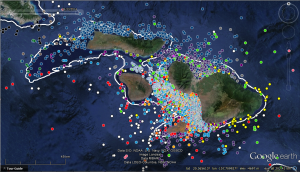

Researchers Complete Second Phase of Maui Tiger Shark Tracking Project

Researchers Complete Second Phase of Maui Tiger Shark Tracking Project

Researchers completed the second phase of a project to observe the movements of tiger sharks caught and tagged around the island of Maui. The study, funded by the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), is in response to a recent uptick in the number of shark attacks recorded around the Valley Isle. Lead scientists Carl Meyer and Kim Holland report that in early 2014 their team caught and released nine tiger sharks in waters off Maui. The near-real-time tracks of these sharks will be added to the eight tracks already on the Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System (PacIOOS) Hawai’i Tiger Shark Tracking web page.

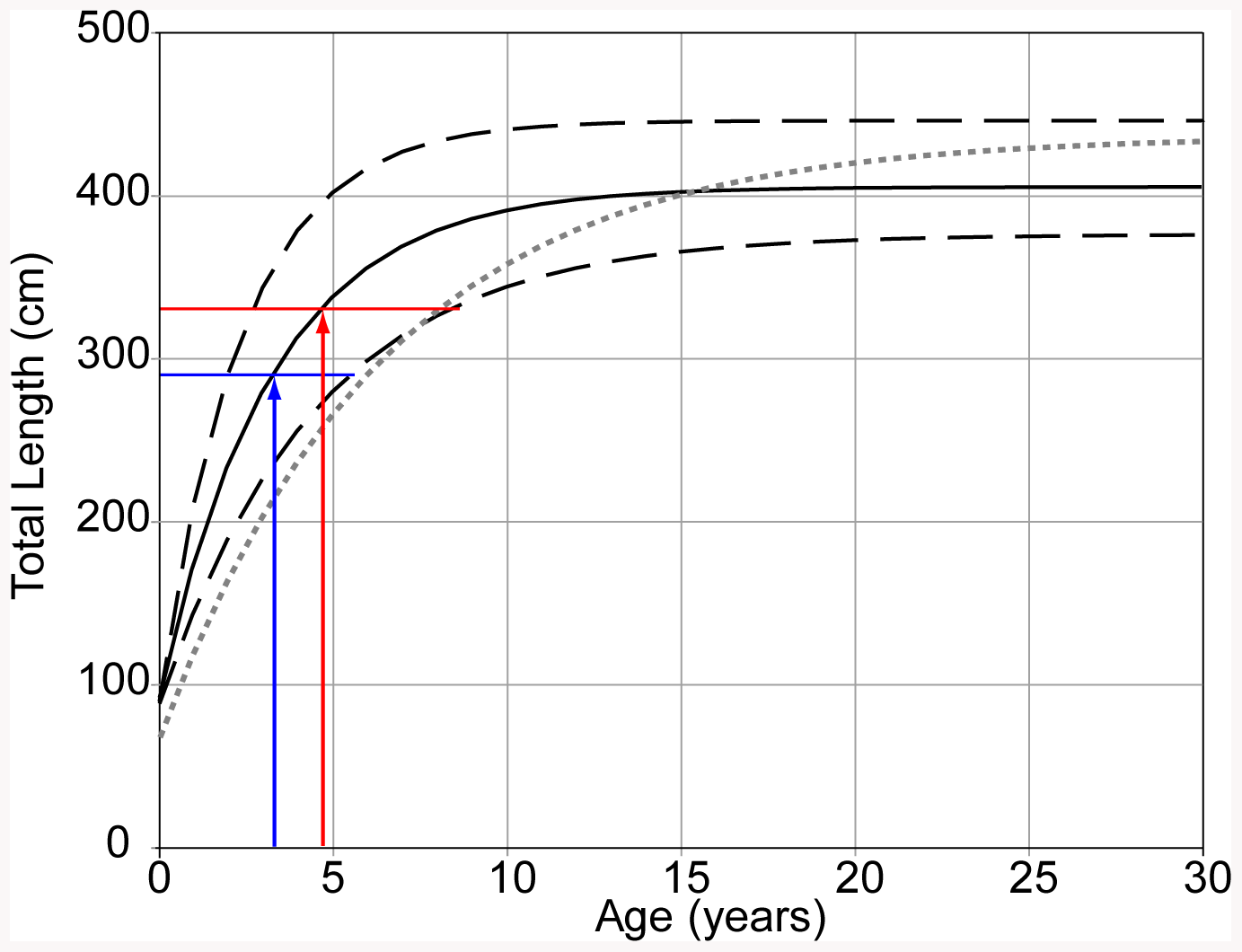

Growth and Maximum Size of Tiger Sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) in Hawaii

Growth and Maximum Size of Tiger Sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) in Hawaii

Since 1993, the University of Hawai’i has conducted a research program aimed at elucidating tiger shark biology, and to date 420 tiger sharks have been tagged and 50 recaptured. We used these empirical mark-recapture data to estimate growth rates and maximum size for tiger sharks in Hawaii. We conclude that tiger shark growth rates and maximum sizes in Hawaii are generally consistent with those in other regions, and hypothesize that a broad diet may help them to achieve this rapid growth by maximizing prey consumption rates.

New PacIOOS Hawai’i Tiger Shark Tracking Web Site

New PacIOOS Hawai’i Tiger Shark Tracking Web Site

After several recent attacks, a new web site hosted by the Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System (PacIOOS) allows people to track the movements of several of the 15 tiger sharks tagged by researchers, led by Carl Meyer and Kim Holland of the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), off Maui in October. Meyer said the initial results are consistent with the wide-ranging behavior seen previously. “They’ve revisited the places where they were originally captured, but they haven’t stayed in any one location for very long. They’re constantly on the move, and the timing of their visits has been unpredictable.”

Female Tiger Sharks Migrate During Fall Pupping Season

Female Tiger Sharks Migrate During Fall Pupping Season

A quarter of the mature female tiger sharks plying the waters around the remote coral atolls of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands decamp for the populated main Hawaiian Islands in the late summer and fall, swimming as far as 2,500 kilometers (1,500 miles), according to new research from University of Florida and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Their report is scheduled for publication in the November 2013 issue of Ecological Society of America’s journal Ecology.